At face value, the Chronicle of Higher Education’s 8 Things You Should Know About MOOCs, a data draw from the recent edX release of data, reads more like 8 Things You Already Know About MOOCs: MOOCs are populated by highly educated individuals, most registrants do not interact, registration is highly Western. Such tepid information makes the article feel like click-bait; anyone following MOOCs over the last 2.5 years could point to prior evidence of these facts the Chronicle article presents as novel.

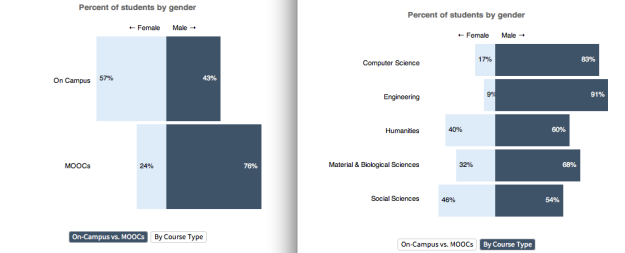

What I found most interesting was the graphic relating to the gender distribution fact: over 3/4 of edX students are male. Again, this is not novel information; the Penn survey in 2013 noted this, data further elucidated by New Scientist magazine. But the Chronicle presents the graphic by first showing gender breakdowns across American college campuses, where 57% of students are female.

It is a pretty stark difference to see a nearly 3 to 2 female to male majority on campus shift to 3 to 1 male to female in the world of MOOCs. One could argue that fewer women than men participating in MOOCs is not necessarily shocking; there are many articles on record showing the STEM field to be male-dominated (some sensational, others more tempered), so this data could be read to support a largely accepted happenstance. However, MOOC research (and EdTech research in general) is almost always instrumental by design, a form of A/B testing that abstracts the system from the environment and fails to account for political, cultural or social elements. Continue reading